Glossary

[CZ] autotypie a pérovka

.......................................................................

Autotype is a term used to designate the HALFTONE printing process. An autotype PROCESS BLOCK would therefore describe one for reproducing photographs or other grayscale works of art. Color photographs can be printed from the transferal of multiple negatives as autotype PROCESS BLOCKS, which are then typically printed in yellow, red, and blue.

Alternately, line etchings indicate images typically originally rendered from pen or black ink linework, or stippling from crayon, pencil, or brush. A line etching can also simply indicate text. Because there is no gradation in color in the line etching, as opposed to a photograph, the transfer of a line etching to a PROCESS BLOCK for reproduction in multiple does not require the use of a SCREEN as in the HALFTONE process. It is still, however, a photomechanical process that prepares the line-drawn image to become a PROCESS BLOCK for printing.

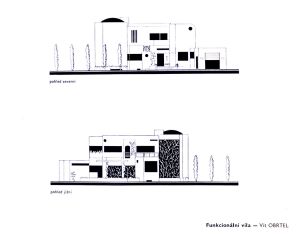

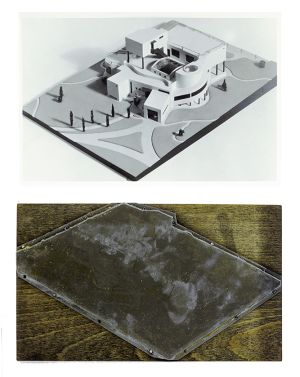

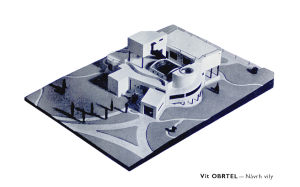

The distinction between a HALFTONE autotype versus line-drawn source is nicely visualized through a set of original drawings, photographs, and PROCESS BLOCK of architectural plans and blueprints by Vít Obrtel, which are held in his archive at the Národní technické muzeum (National Technical Museum) in Prague. Pictured here are two process blocks rendered from line drawings of his 1933 Funkcionální vila (Functional Villa) from north and south views. In another example, a three-dimensional model for a different villa has been photographed; the negative of this photograph would have then been used for transferring the image via the HALFTONE SCREEN process to a metal plate and finally affixed to type-high wood ready for LETTERPRESS printing. The result of creating these PROCESS BLOCKS—which is their printing in serial form—can be found in the Fall 1933 issue of Kvart, an architectural magazine under Obrtel’s editorship.

i

Bohumil Dobrovolný and Karel Andrlík, Hokrův technický slovník naučný [Hokr’s instructional technical dictionary] (Prague: Josef Hokr, 1943), 46. NK. https://ndk.cz/uuid/uuid:431998493183aab163d0c600b662b891

i

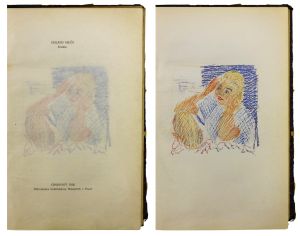

Richard Martinčík, Úvod do grafického průmyslu [Introduction to the graphic design industry] (Brno: Grafický klub, 1922), n.p. https://ndk.cz/uuid/uuid:55c2d92f-716e-4963-a441-0d715a9c65a1https://ndk.cz/uuid/uuid:841c424e-957f-4444-99b7-70ac85263c9d

i

Richard Martinčík, Úvod do grafického průmyslu [Introduction to the graphic design industry] (Brno: Grafický klub, 1922), n.p. https://ndk.cz/uuid/uuid:bd93cd9c-ce77-44e1-a5c9-40da68a1fb13https://ndk.cz/uuid/uuid:2b53d4e1-6343-4077-8483-c99ad14e47eb

i

Process block for Vít Obrtel, Funkcionální vila, pohled jižní [Functional Villa, view from the south]. Vít Obrtel Archive (hereafter VO Archive), Národní technické museum (National Technical Museum, hereafter NTM) in Prague. NTM, Archive of architecture and building, Vít Obrtel Archive, NAD 151, kt. 001, č. 53, 71/8. Photo: Jiří Odvárka / © Vít Obrtel – heirs c/o DILIA, 2025.

i

Process block for Vít Obrtel, Funkcionální vila, pohled jižní [Functional Villa, view from the north]. NTM, Archive of architecture and building, Vít Obrtel Archive, NAD 151, kt. 001, č. 53, 71/8. Photo: Jiří Odvárka / © Vít Obrtel – heirs c/o DILIA, 2025.

i

Vít Obrtel, “Funkcionální vila,” Kvart, no. 3 (Fall 1933): n.p. NK ČR, 54 F 025291/Roč. 2. 1933–1935, Photo: Jiří Odvárka / © Vít Obrtel – heirs ℅ DILIA, 2025.

i

Vít Obrtel, Návrh vily [Plan for a villa], Vít Obrtel Archive, Národní technické museum (National Technical Museum, Prague).

i

Vít Obrtel, “Návrh vily” [Plan for a villa], Kvart, no. 3 (Fall 1933?). Clementinum Library, Prague.

[CZ] štoček

.......................................................................

The block (i.e., from wood, linoleum, or metal) has been a printing form used for centuries. It is described in the Encyclopedia of Printing, Photographic, and Photomechanical Processes as

"a block of wood or metal, or metal plate backed by either wood or metal, and having a typographic (relief) printing surface. It may be a process block (produced photographically), a woodcut, in the production of which photography may or may not play a part, an ELECTROTYPE, or STEREOTYPE. “Block processes” include all those processes in which, by the aid of photography, a relief surface is produced, capable of being printed from […] an ordinary printing press together with letterpress."(1)

Some of these processes precede the history of photography—for instance, in the case of engraving by hand, they make use of a set of tools and blocks of wood or linoleum—and others are connected to photomechanical processes in which the image results after a chemically treated metal plate becomes etched through the application of light.

While in English the terms cliché (adopted from the French), plate, and block, are perhaps most commonly applied to describe this printing object, use of the term process block, as provided in the Encyclopedia of Printing, Photographic, and Photomechanical Processes, helps to pinpoint those blocks that were created with the introduction of photomechanical processes. The work to be reproduced—which could be a drawing or another photograph or print, for instance—would be transferred onto a metal plate through a light-sensitive process. In order to produce a printed image with a fuller range of gray tone, HALFTONE images could be produced using a SCREEN.

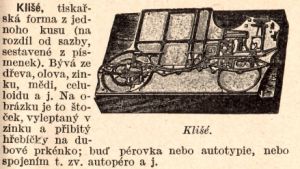

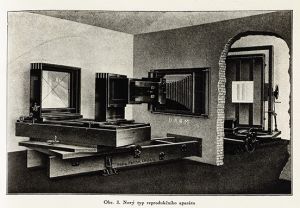

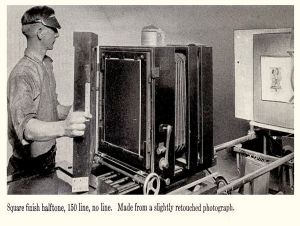

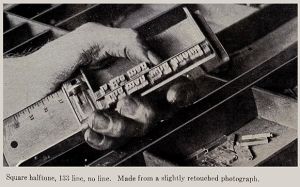

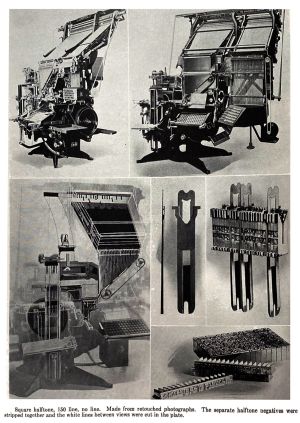

In the Czech context, the cliché, transliterated as klišé, has been defined in Hokrův technický slovník naučný (Hokr’s instructional technical dictionary) as “a printer’s form from a single unit (as distinct from typesetting, which is composed of multiple letter forms). It has been made from wood, lead, zinc, copper, celluloid, etc. The image is affixed to the process block [štoček], etched into the zinc and nailed onto an oak block; it can be derived from a line drawing or HALFTONE AUTOTYPE.”(2) A 1928 article in the Czech trade magazine Typografia, entitled “Výroba štočků knihotiskových” (The production of letterpress process blocks), notes that in the Czech context, the plate used in printing from process blocks/štočky was typically from zinc (as it is less expensive than copper), and describes how the plate would be treated with a light-sensitive chemical so that when a negative was affixed to it and light applied, an image would be etched into the surface and subsequently be printed.(3) Accompanying the article, a set of images illustrate the machines by which a process block is created via photomechanical reproduction. The massive photomechanical instrument is, for its size and ability to isolate light, likened to a darkroom.(4) In the interwar period, images were typically reproduced from process blocks and printed by LETTERPRESS (or OFFSET) technologies.

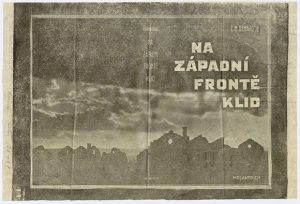

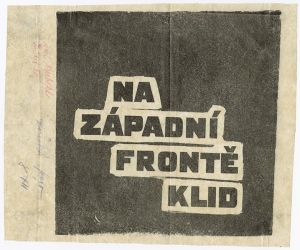

The archival holdings of the publishing house Melantrich, kept at the Památník národního písemnictví (Museum of Czech Literature, PNP) in Prague, offer a helpful illustration of how process blocks were ordered by publishers from printing firms, and what they cost. For the Czech translation by Bohumil Mathesius of All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque, we can see the design for the cover inked on two sheets of transparent paper. One is a reproduction of a photographic image of the hollow façades of a bombed-out town below a cloudy sky, rendered in gray tones from a HALFTONE process. Additionally, a second sheet bears the text of the title in bold black, a LINE-ETCHING process. An accompanying handwritten note indicates that the fee for one HALFTONE (“AUTO”) process block, to be printed in black, with a surface area just over 600 square centimeters is 365.50 koruna, and one LINE-ETCHED (“pérovka”) process block of almost 88 square centimeters, to be printed in red, will cost 44 koruna. Looking to the printed and published outcome of the book, with a cover design by František Muzika, we can indeed see the title was inked in red juxtaposed with the photographic image in black. The text of the author’s name is uninked negative space, which would have precluded the cost of producing more process blocks for printing in another color.

.......................................................................

Notes:

(1) Bohumil Dobrovolný and Karel Andrlík, Hokrův technický slovník naučný [Hokr’s instructional technical dictionary] (Prague: Josef Hokr, 1943), 245. Original: “tiskařská forma z jednoho kusu (na rozdíl od sazby, sestavené z písmenek). Bývá ze dřeva, olova, zinku, mědi, celuloidu a j. Na obrázku je to štoček, vyleptaný v zinku a přibitý hřebíčky na dubové prkénko bud’ pérovka nebo autotypie.”

(2) See the unattributed article, “Výroba štočků knihotiskových” [The production of letterpress process blocks], Typografia 35, nos. 1–3 (1928): 77.

(3) Stade, “Fotomechanické způsoby reprodukční” [Photomechanical methods of reproduction], Typografia 35, nos. 1–3 (1928): 75.

(4) Luis Nadeau, Encyclopedia of Printing, Photographic, and Photomechanical Processes: A Comprehensive Reference to Reproduction Technologies, Containing Invaluable Information on over 1500 Processes, 2 vols. (Fredericton, NB: Atelier L. Nadeau, 1994), 1:47.

i

Dictionary entry in Bohumil Dobrovolný and Karel Andrlík, Hokrův technický slovník naučný [Hokr’s instructional technical dictionary] (Prague: Josef Hokr, 1943), 245. AV ČR Library, F 73195. Photo: ÚDU AV ČR.

i

Images depicting the halftone photomechanical process and related machines in Stade, “Reprodukční fotografie” [Reproduction photography], Typografia 35, nos. 1–3 (1928): 74–76. UPM Library.

i

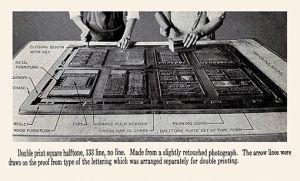

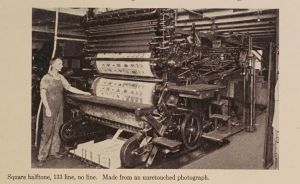

Charles W. Hackleman, Commercial Engraving and Printing (Indianapolis, IN: Commercial Engraving Publishing Co., 1921, 1924), 251. Courtesy of Jim Horton. Photo: Barbara Brown.

i

Neubert a synové [Neubert and Sons] sample print for the production of process blocks for the cover of Erich Maria Remarque, Na západní frontě klid [All Quiet on the Western Front] (Prague: Melantrich, 1929). LA PNP, Melantrich Archive, correspondence Neubert V. a synové. Photo: PNP / © František Muzika/OOA-S, 2025.

i

Neubert a synové [Neubert and Sons] sample print for the production of process blocks for the cover of Erich Maria Remarque, Na západní frontě klid [All Quiet on the Western Front] (Prague: Melantrich, 1929). LA PNP, Melantrich Archive, correspondence Neubert V. a synové. Photo: PNP / © František Muzika/OOA-S, 2025.

[CZ] světlotisk

.......................................................................

Collotype is a photo-gelatin PLANOGRAPHIC transfer process. Invented in 1855 by Alphonse Poitevin, it is a “dichromated colloid process [that] uses the tanning effect of light on dichromated gelatin, whereby the hardened parts retain greasy ink that can be transferred onto paper, porcelain, and a variety of other supports.”(1) Collotype is considered the precursor to PHOTOLITOGRAPHY. It was improved and commercialized by 1860 by F. Joubert in France, under the name phototype, and from there various improvements were made under different names, including by a Czech artist based in Prague, Jakub Husník.

Collotype is notable for the high quality of reproductions it can produce and has the advantage of accommodating prints with any amount of white margin on the page. It is a technique that can be used for color as well as high-quality photographic reproduction, for instance in the use of picture postcards.

The first rotary collotype was developed in 1873 by Joseph Albert in Munich and adapted to offset processes by 1940 using flexible metal sheets.

.......................................................................

Notes:

(1) Nadeau, Encyclopedia of Printing, Photographic, and Photomechanical Processes, 1:73.

[CZ] polotón

.......................................................................

The halftone process, according to Charles W. Hackleman, is “a mechanical method of photographically reproducing in a printing plate the details of a photograph, drawing, painting, or an object itself, including all the gradations of color.”(1) Through this process, it is possible to reproduce an image in a range of tones, with the use of a SCREEN that would divide the original image into a series of dots on a grid. It was in use and described by Henry Fox Talbot by 1852 and in general use around 1890. The halftone process was initially produced for RELIEF printing before being adapted for PLANOGRAPHIC printing, such as PHOTOLITOGRAPHY.

The Practice of Printing, first published in 1926 in the United States, describes and visualizes the photomechanical process by which images are transferred as halftone onto metal:

"The copy to be reproduced is placed on a frame in front of the camera […], focused for size, and a negative is photographically developed on the sensitive surface of a sheet of metal, which is to become a LETTERPRESS printing plate. The copy is photographed through a SCREEN which converts the image into a pattern of dots. […] The plate is then chemically etched until the dots stand out in sharp relief above the rest of the plate.

After the plate is etched, it is sent to the finishing-room to be trimmed, routed, and beveled, for mounting. […]

Copy for halftones usually consists of photographs or wash drawings, although almost any manner of copy might be reproduced by this process, if desired."(2)

A reproduction could be obtained from printing from the surface of the halftone plate, typically of zinc or copper mounted on wood (i.e., a PROCESS BLOCK) and used for LETTERPRESS RELIEF PRINTING, or also in the printing techniques of PHOTOLITOGRAPHY and to some extent ROTARY PHOTOGRAVURE.

.......................................................................

Notes:

(1) Hackleman, Commercial Engraving and Printing, 242.

(2) Ralph W. Polk and Edwin W. Polk, The Practice of Printing [1926], 7th ed. (Peoria, IL: Chas. A. Bennett Co., Inc., 1971), 268–269. The term “letterpress printing plate” is used here as a “general, all-inclusive term” for what I am describing as the process block (ibid., 267).

[CZ] hlubotisk, stírací hlubotisk a rotační stírací hlubotisk

.......................................................................

Intaglio processes date back to the fifteenth century, were used extensively into the mid-nineteenth century, and include a range of printing methods “in which the lines, dots, grain, or other elements of the engraving are sunk in the plate, so that the depressions are filled with ink for printing, as distinguished from RELIEF PROCESSES.”(1) Unlike with RELIEF and PLANOGRAPHIC printing processes, intaglio printing requires that paper first be dampened, in order to pick up the ink that remains in the etched plate when run through the press.

Photogravure is an intaglio engraving process which, instead of using a screen and the HALFTONE process, employs a fine grain burnt through a photographic negative, with the use of a gelatin mold and copper plate.

Rotary photogravure, or simply, rotogravure, similar to OFFSET printing, is an innovation that came into general use around 1907 in which the copper printing plate is a rounded cylinder. Unlike photogravure, rotogravure does utilize a SCREEN and a positive, made from a retouched negative. The steps in moving from the image to be reproduced and its printed reproduction are, in sum, as follows:

"the preparation of the negative and positive, or transparency and its retouching; preparation of the resist; a separate printing of the transparency and the SCREEN on to a gelatin carbon tissue; the transferring of the resist to the copper cylinder; and the etching of the cylinder for printing on a rotary press."(2)

.......................................................................

Notes:

(1) Nadeau, Encyclopedia of Printing, Photographic, and Photomechanical Processes, 1:133.

(2) Hackleman, Commercial Engraving and Printing, 566. The “resist” is a sensitized piece of carbon tissue placed on the film side of a glass positive.

[CZ] knihtisk (tisk z výšky)

.......................................................................

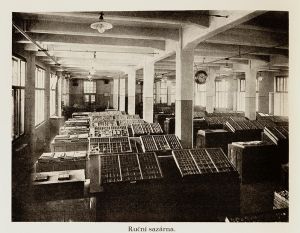

Relief printing encompasses all the processes by which raised characters (letter forms) or plates are inked and pressed to paper, which can leave an impression on the page. Evidence of relief printing dates back to ancient times; well into the twentieth century, letterpress printing, a form of relief printing, was the most widely used commercial printing form. Moveable type set by hand, woodcuts, linocuts, and PROCESS BLOCKS/štočky can all be set and locked into a chase (see second image below) and then printed. Modern printing presses, such as the Vandercook proof press—in which the type is arranged in the bed of the press—or the Heidelberg platen press, which has a clam-shell-like hinge mechanism, ink the type and/or plate with rubber rollers and then press the inked surface into a piece of paper.

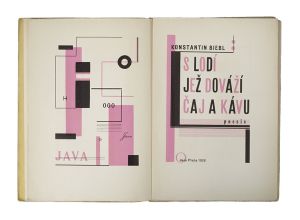

In the context of Czechoslovakia in the interwar period, Devětsil editions produced in collaboration with the printer Kryl a Scotti in the small town of Nový Jičín and publisher Odeon in Prague show the artistic capacity of letterpress printing, especially in the experimental arrangement of moveable type to reproduce Karel Teige’s designs for “typographic montages,” which illustrate volumes of poetry by Konstantin Biebl published in 1928 (S lodí jež dováží čaj a kávu [With the ship that carries tea and coffee] and Zlom [Break]).

The need for handset type—while still in use even today, largely in the context of artists’ books—began to be replaced by typesetting machines after Ottmar Mergenthaler’s invention of the Linotype, patented in the United States in 1894. It would be the most commonly used of the commercial typesetting machines, of which there were also competitors such as the Monotype and Intertype—the latter of which first arrived in Czechoslovakia only in 1921 but was then used widely. This typesetting machine revolutionized the speed by which words could be brought to print by making it possible to cast a whole line of metal type, directed by a technician at a keyboard, and then assembled and locked into the chase to be printed via letterpress. Reports on advancements to the Linotype and other machines used for printing are ample on the pages of Typografia in the 1920s: an article in 1927, for instance, reports on the development of three new models and their adaptations to accommodate the needs of the Czech alphabet.(1) By that time, these new machines were utilized alongside other new technologies, such as the photomechanical production of PROCESS BLOCKS, STEREOTYPES, ELECTROTYPES, OFFSET PRINTING, etc. to open up new possibilities in the entire printing process.

.......................................................................

Notes:

(1) František Lexa, “Tři nové modely Linotype a některé jiné novinky” [Three new Linotype models and some other news], Typografia 34, no. 4 (1927): 62.

i

Reproduction of a photograph of the composing stick used for setting type by hand in Hackleman, Charles W. Hackleman, Commercial Engraving and Printing (Indianapolis, IN: Commercial Engraving Publishing Co., 1921, 1924), 439. Courtesy of Jim Horton. Photo: Barbara Brown.

i

Annotated photographic illustration of a printing form being locked in the chase in Hackleman. Charles W. Hackleman, Commercial Engraving and Printing (Indianapolis, IN: Commercial Engraving Publishing Co., 1921, 1924), 449. Courtesy of Jim Horton. Photo: Barbara Brown.

i

Reproductions of photographs in Method Kaláb, “Průmyslová tiskárna v Praze” [Industrial print shop in Prague], Typografia 33 (1926): 240–242. UPM Library, IaC168/1926. Photo: ÚDU AV ČR.

i

Cover art by Karel Teige for Konstantin Biebl, S lodí jež dováží čaj a kávu [With the ship that carries tea and coffee], 2nd ed. (Prague: Odeon, 1928). Courtesy of the author. Photo: ÚDU AV ČR.

i

Reproduction of photographs illustrating the Linotype, matrices, and slugs, Charles W. Hackleman, “The Linotype,” in Commercial Engraving and Printing (Indianapolis, IN: Commercial Engraving Publishing Co., 1921, 1924), 433. Courtesy of Jim Horton. Photo: Barbara Brown.

i

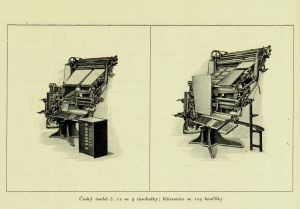

“Czech model no. 13” in František Lexa, “Tři nové modely Linotype a některé jiné novinky” [Three new Linotype models and some other news], Typografia 34, no. 4 (1927): 62. Library of the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague.

[CZ] litografie a fotolitografie (tisk z plochy)

.......................................................................

Literally meaning “writing on stone,” lithography describes a planographic printing process that relies on the principle that oil and water repel each other. A drawing from a greasy ink is made directly onto a flat stone. The stone is then moistened with water, absorbing it in areas not covered in the drawing. An oil-based ink is then applied to the whole stone with a roller, and the ink only adheres to the drawing, while it is repelled by the water on the rest of the stone. Then paper is applied to the stone with pressure, and the design can be pulled up. The lithographic process was invented in 1798 by Alöys Senefelder, then living in Munich, though born in Prague.

There are many mediums from which a source image might be derived, one being photography. Photolithography was adapted to print photographic works, initially a quite technical and difficult process. The technique is described in the Commercial Engraving and Printing manual, first printed in the United States in 1921:

"In photolithography the image is first obtained photographically through the action of light upon a sensitized film, as in other photomechanical processes, but after transferring the image to the stone or plate the method employed in printing is exactly the same as in other branches of lithography. The image may be secured on the plate by transferring directly from the photographic film; by transferring from an engraved INTAGLIO plate; or by photoprinting directly on the metal. It is necessary that the subject to be copied should consist of notable lines and dots, and before the discovery of the HALFTONE process only LINE DRAWINGS could be reproduced by photolithography."(1)

Photolithographic plates were utilized in book and newspaper printing as early as the 1860s and 1870s, when they emerged as an alternative to wood engravings for producing illustrations. Photolithography, like the production of relief process blocks, made use of the halftone for rendering images in gray scale and multiple colors.

.......................................................................

Notes:

(1) Charles W. Hackleman, Commercial Engraving and Printing (Indianapolis, IN: Commercial Engraving Publishing Co., 1921, 1924), 502.

[CZ] matrice

.......................................................................

In LETTERPRESS printing, the matrix is the unit of composition used for machines of mechanical composition, such as the Linotype. The matrices, which are small brass dies that hold the information of the individual letter forms, are assembled in the desired order of composition. With each press of a key, the machine operator releases the corresponding matrix: these are assembled in a row and transferred to a casting position. Molten lead is prepared in a heated metal pot and, from there, pressed upon the line of matrices so that a “slug,” or line of type, is produced and prepared for printing. Once a series of slugs is assembled and the printing complete, the lead can go back into the metal pot to be melted down and reused for setting more type. The innovation of the use of the matrix to generate lines of type obviated a dependence on the labor-intensive model of setting individual pieces of moveable type by hand and drastically sped up the process of printing text. A recent documentary, Linotype: The Film, presents the history of the Linotype and its revolutionary contribution to print history.

The term matrix also appears in the context of producing HALFTONE plates, but this is not a synonymous process. In this case, it refers to the matrix of dots of the printing surface that can produce an image in gray scale or color.

[CZ] offset

.......................................................................

Both PHOTOLITHOGRAPHY and offset are PLANOGRAPHIC processes. Ultimately, the two are more or less synonymous, but with the innovation of offset printing, the photographic image could now be transferred to a rubber roller, and from there, to paper. As detailed in Commercial Engraving and Printing, it “derives its name from the fact that the printed impression is made from a thin flexible metal plate curved to fit a cylinder, first upon a revolving cylinder covered with a rubber blanket, which in turn ‘offsets’ it on to the paper.* The use of the rollers allowed for greater flexibility. Offset was picked up for use in book printing from 1906 onward, and the first instance of color HALFTONE offset printing is the Process Year Book of 1909–1910, printed in England. Eventually, the offset process was utilized more frequently in reproducing photographic images than LETTERPRESS processes were.

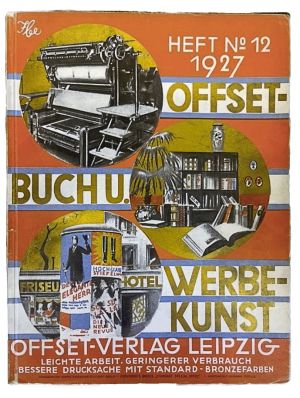

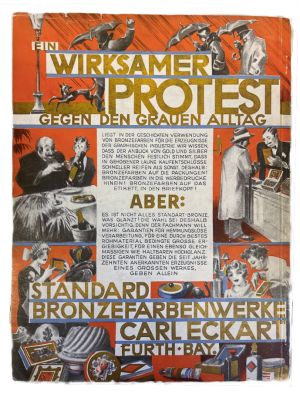

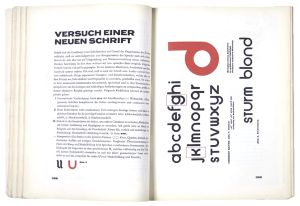

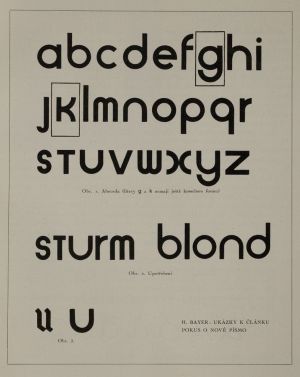

A periodical with the apt title Offset, published in the 1920s in Leipzig, Germany—a center in the history of printing and bookmaking—showed off the impressive possibilities of the technology for illustrations in a range of saturated colors. As noted in one advertisement, it amounted to “a true protest against the gray of everyday” (see figure 16). A special issue of Offset from 1925 was dedicated to the Bauhaus school in Germany; several of the texts and images that appeared there were then picked up, translated, and reproduced in the Czech trade periodical Typografia, indicating that Czech printers and typographers were keeping a close eye on the work of their peers in Germany.

* Hackleman, Commercial Engraving and Printing, 503.

i

Richard Martinčík, Úvod do grafického průmyslu [Introduction to the graphic design industry] (Brno: Grafický klub, 1922). https://ndk.cz/uuid/uuid:1bf12b35-3996-45ba-8a78-16b14fed744ahttps://ndk.cz/uuid/uuid:18230235-4952-4c06-9942-71132992229c

i

Advertisement for an offset machine in Offset, Buch- und Werbekunst [Offset, book and advertising art], no. 1 (1927): n.p. UPM Library.

i

Illustration of an offset press in Charles W. Hackleman, Commercial Engraving and Printing (Indianapolis, IN: Commercial Engraving Publishing Co., 1921, 1924), 502. Courtesy of Jim Horton. Photo: Barbara Brown.

i

Front cover of Offset no. 12 (1927). Jihočeská vědecká knihovna v českých budějovicích.

i

Back cover of Offset no. 12 (1927). Jihočeská vědecká knihovna v českých budějovicích. ČB 1.117/1927.

i

Herbert Bayer, “Versuch einer neuen Schrift” [Attempt at a new type face], Offset no. 7 (1926): 398–399.

i

Herbert Bayer’s script in Typografia 34, no. 3 (March 1927): 41. Library of the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague.

[CZ] rastr

.......................................................................

HALFTONES are produced with the use of a screen inserted between the copy to be reproduced and the plate in the large-scale photo apparatus. The screen may be fine, medium, or coarse, depending on the number of lines, and is typically at a 45-degree angle. The best screens were actually produced by engraving parallel lines onto sheets of glass and cementing two together at right angles. When light is applied through the lines of the screen, dots are etched via a chemical process into the plate.

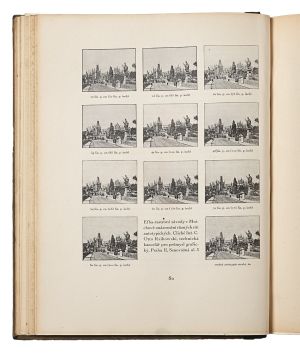

In the Czech periodical Typografia, a reproduction of a photograph of the Charles Bridge in Prague offers comparative results based on the number of lines in a screen, displaying the level of detail available in a print based on the density of dots in the resulting HALFTONE for use as a PROCESS BLOCK in LETTERPRESS printing.

Similarly, a playful illustration in the German magazine Offset shows how the same principle applies when the screen is used in HALFTONE PHOTOLITOGRAPHIC processes.

In the case of PHOTOGRAVURE, the screen is similar but has thinner lines than in the HALFTONE process, and the positive, rather than negative, is exposed.

i

Images in “Výroba štočků knihotiskových” [The production of letterpress process blocks], Typografia 35, nos. 1–3: 80. ÚČL AV ČR Library, bohemistický fond, 20 GX 1. Photo: ÚDU AV ČR.

i

Illustration in Offset 12 (1927): 587. Jihočeská vědecká knihovna v Českých budějovicích.

[CZ] stereotypie a electrotypie

.......................................................................

A stereotype indicates the duplication of a printing plate comprised of type. It is made from taking a cast of a MATRIX, itself made by taking a mold of the original printing surface. Typically, the mold is derived from moist paper pulp, i.e., papier-mâché. What is known as the stereotype process was first patented in 1725 by the Scottish inventor William Ged. The actual term stereotype (in French, as stéréotypie) was coined some years later in Paris by Firmin Didot. The process for making the stereotype is described by Hackleman in Commercial Engraving and Printing:

"[T]he damp paper is placed on the type form [...] covered with a blanket, and pressure is applied to obtain the impression or mould either by beating with a brush or by the use of a matrix rolling machine. [...] The form with the matrix still on it is then transferred to a steam or electrically heated table and the matrix dried while under pressure, when it is removed from the form. The matrix is then placed on the casting box. [...] The box is tilted in an upright position and the molten metal is poured or pumped in. It hardens almost instantly."(1)

As described in the 1922 Úvod do grafického průmyslu (Introduction to the graphic design industry) by Richard Martinčík, “the goal of the stereotype was to conserve the use of letterforms and the occasion of repetitive typesetting, speeding up production through the casting.”(2)

Curved stereotype plates came into common use in the newsroom for printing newspapers in the early 1960s. The process is not suitable for producing molds from HALFTONE plates. In that case, an electrotype is needed, preferably made from a wax or lead mold.

.......................................................................

Notes:

(1) Hackleman, Commercial Engraving and Printing, 364–365.

(2) Richard Martinčík, Úvod do grafického průmyslu [Introduction to the graphic design industry] (Brno: Grafický klub, 1922), 137. Original: “Účelem stereotypie je setřiti písmo a případné opakování sazby, usnadniti odlitkem rychlé její zhotovení.”

i

Jana Vránková, Olga Frídlová, and Pavel Pohlreich, Katalog expozice: Tiskařství [Printing: Catalogue of the Exhibition] (Prague: Národní technické muzeum, 2015), 81.

[CZ] zinkografie

.......................................................................

LINE ETCHINGS, according to Charles W. Hackleman in the Commercial Engraving and Printing manual, are “the simplest and least expensive method of making printing plates by the photo-mechanical process. They are usually made on zinc and for that reason are commonly called ‘zinc etchings.’”(1) The zinc etching process, or zincography, relies on black-and-white, not HALFTONE, copy. Although the process of producing the zinc etching is similar to HALFTONE, it is not photographed through a SCREEN, as in the latter process. Thus, a LINE ETCHING cannot be produced directly from a photograph, for instance. Copy typically originates from pen drawings, and shading effects are created through the use of lines, dots, or stippling.

.......................................................................

Notes:

(1) Hackleman, Commercial Engraving and Printing, 217.

Introduction

Glossary of terms for photomechanical printing developed in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries

Compiled by Meghan Forbes

...............................................

William Henry Fox Talbot, one of the originators of photography, described before the Royal Society in London on January 31, 1839, his discovery of a process of “photogenic drawing” and proposed some possible further uses for this new technology, emphasizing its documentary and reproductive capacities.(1) It was not much later, already in 1852, that he discovered that if a dry film of gelatin or albumen solution containing dissolved chromate or bichromate salts were to be exposed to light through a photographic negative, the parts of the film that are exposed to light become insoluble while the rest can be washed away. This process was immediately adapted for the purposes of photomechanical engraving, which dramatically opened up the possibilities for producing plates from which to reproduce images in print. Various photomechanical processes developed from there, including line etching, halftones, and photolithography, which are detailed in this glossary.

By the turn of the twentieth century, photography and related photomechanical processes were in common use, and the reproduction and distribution of images in popular print, such as magazines, newspapers, and books, intensified. The capacity for increasingly accessible modes of image dispersal did not go unnoticed by artists, of course, and avant-garde printed matter made innovative use of these new technologies. In my book Technologies for the Revolution: The Czech Avant-Garde in Print (Artefactum/Karolinum Press, 2025), I detail some of the outcomes of this engagement. Here, I introduce a small selection of the most essential terms used in the processes of letterpress and offset printing that adapted the invention of photography to preexisting modes of print production.

The glossary is by no means comprehensive; there are already ample technical manuals and encyclopedias to that end. Rather, I hope what follows is a quick and handy guide for readers with no practical background in printing to better understand how text and image were usually printed in the period from the mid-nineteenth to mid-twentieth century (with a focus on North American and Central European sources).

...............................................

Notes:

(1) William Henry Fox Talbot, “Some Account of the Art of Photogenic Drawing, or, The Process by Which Natural Objects May Be Made to Delineate Themselves without the Aid of the Artist’s Pencil,” in Photography: Essays and Images; Illustrated Readings in the History of Photography, ed. Beaumont Newhall (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1980), 26.

...............................................

Major sources that were regularly consulted in the compilation of this glossary are:

• Bohumil Dobrovolný and Karel Andrlík, Hokrův technický uovník naučný [Hokr’s instructional technical dictionary] (Prague: Josef Hokr, 1943).

• Charles W. Hackleman, Commercial Engraving and Printing (Indianapolis, IN: Commercial Engraving Publishing Co., 1921, 1924).

• Luis Nadeau, Encyclopedia of Printing, Photographic, and Photomechanical Processes: A Comprehensive Reference to Reproduction Technologies, Containing Invaluable Information on over 1500 Processes, 2 vols. (Fredericton, NB: Atelier L. Nadeau, 1994).

• Richard Martinčík, Úvod do grafického průmyslu [Introduction to the graphic design industry] (Brno: Grafický klub, 1922).

• Ralph W. Polk and Edwin W. Polk, The Practice of Printing [1926], 7th ed. (Peoria, IL: Chas. A. Bennett Co., Inc., 1971).

• Jana Vránková, Olga Frídlová, and Pavel Pohlreich, Katalog expozice: Tiskařství (Prague: Národní technické muzeum, 2015). English edition: Vránková, Frídlová, and Pohlreich, Printing: Catalogue of the Exhibition, trans. Olga Piperová Taušová (Prague: Národní technické museum, 2018).

...............................................

Some of the text in this glossary is adapted from my book:

• Meghan Forbes, Technologies for the Revolution: The Czech Avant-Garde in Print (Prague: Artefactum/Karolinum Press, 2025).

Unless otherwise noted, all translations of quoted passages are my own.